Game Addiction Through a Design Lens

How do videogame narrative elements contrast with ludic aspects in terms of their manipulation of player attention and affect?

Context

This is my final Thesis, produced during my undergraduate degree in Game Arts and exploring the question: “How do video game narrative elements contrast with ludic aspects in terms of their manipulation of player attention and affect?” I have intentionally left it unedited from the version I submitted (aside from formatting), as a relic of my thinking and writing skills at the time. I will produced revised content on this subject in the future.

Having struggled with the addictiveness of games for all of my life, I wanted to push back on certain forms of game design which promote addictive gameplay loops. Disclaimer: This is not a psychological study and focuses mostly on the media itself.

The following is a relatively long read, at approximately 6600 words. Most articles I produce will be much shorter.

Thesis

The videogame industry holds a great interest in the length of time that audiences can engage with games. Much of the marketing during the lead up to Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) focused on its allegedly vast content, such as this article which boasts that ‘One Dev Played Over 175 Hours Of Cyberpunk 2077 And Still Hasn't Beaten It’ (Gameinformer:2020:Online), attempting to build anticipation for the game’s release. Consequently, videogames have received criticism for being time-consuming and addictive. Rob Cover addressed this issue, stating that he sees “the connection between drug addiction and gaming addiction (as) more than a metaphorical comparison” (2006:online). This dissertation will explore those aspects of game design which absorb the player and invite comparisons of this nature. A player’s investment in a game will be assessed by observing attention, which can be defined as the specific length of time a player engages with a product, and Erik Shouse’s principle of affect which ties to emotions and retention, in Feeling, Emotion, Affect (2005); this will indicate not only the time one plays a game, but also the manner of a player’s engagement after this directly observable duration. Thomas Davenport and John Beck’s The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business (2001) will inform definitions and ideologies of the attention economy.

Once these broad ideas are sufficiently explored, the focus will shift to videogame specific concepts and the lenses that are used to examine them: Ludology and Narratology, which each identify gameplay and narrative, respectively, as the quintessential quality of the videogame. Ludology will be understood through works such as Jesper Juul’s A Clash between Game and Narrative (1999) and narratology with Janet Murray’s Toward a Cultural Theory of Gaming (2006). This dissertation will use this understanding of games to determine the difference between the duration of attention and affect garnered from narrative, against ludic elements. Additionally, there will be an effort to balance the discussion by acknowledging the different benefits games can have, such as the communicating of ideas through procedural rhetoric, established in Ian Bogost's Persuasive Games : The Expressive Power of Videogames (2007).

Literature Review

The Attention Economy is a concept often applied to games. In understanding it, a definition of attention is needed. According to Davenport and Beck, “Attention is focused mental engagement on a particular item of information. Items come into our awareness, we attend to a particular item, and then we decide whether to act” (2001:21). Necessarily, to act within any particular game (the ‘Item of information’), the player focuses on what is happening and inputs commands accordingly, allowing this concept to be easily observed in the context of videogames. Competition in the industry arises because:

“Attention is very, very desirable, in some ways infinitely so, since the larger the audience, the better. And, yet, attention is also difficult to achieve owing to its intrinsic scarcity. That combination makes it the potential driving force of a very intense economy.” (Goldhaber, 1997:n.p.)

The idea at the core of almost every facet of the attention economy is that attention is a finite resource, limited by the retentional capacity of each individual. Goldhaber recognises that profit, reputation, and other desirable gains are enabled by attracting and maintaining attention. This view presents player attention as something to be coveted and fought over by corporations and puts emphasis on the quantitative; how much time can a player be held in one game or franchise? However, attention is not always a rigid concept. James Ash states that “videogame designers utilize techniques of what [he] term[s] ‘affective amplification’ [which] seek to modulate affect” (2012:n.p.) This statement cannot be decoded without a concrete understanding of what ‘affect’ is.

“For the infant affect is emotion, for the adult affect is what makes feelings feel. It is what determines the intensity (quantity) of a feeling (quality), as well as the background intensity of our everyday lives (the half-sensed, ongoing hum of quantity/quality that we experience when we are not really attuned to any experience at all.” (Shouse, 2005:online)

In short, affect is a mediator between emotion and rationality. It determines the intensity of feelings so that the subject can respond, much like pain incites one to remedy a harmful situation. Shouse also identifies a “background intensity” which is “ongoing”, suggesting both that the emotion is persistent and can achieve varying levels of potency. By extension, Ash’s ‘affective amplification’ is about how affect is deliberately manipulated in the player, through videogame media, to produce specific experiences. The sustained period of thinking about a game suggests that it exerts an influence strong enough to take up part of a player’s conscious attention, and hints at how games of shorter length have been able to survive alongside their competitors. Affect asserts that attention is not just quantitative, but has qualities based on the specific feelings that a player experiences. Feelings can be positive or negative or intense or subdued. As such, there is an implication that a game can exist as more than just a pastime; the player can sit with the experience and continue to feel investment, whilst attending other tasks. Therein lies a possibility for both the business and player to benefit. Each game in a franchise does not need to occupy the player physically for an excessive amount of time. Rather, if each game can successfully deliver a positive impression for the audience, they symbiotically contribute to the viability of the intellectual property (IP): the collective copyrighted content of an idea. The Star Wars (1977) IP was sold to Disney (1923) for “$4.1 billion in stock and cash” (Forbes:n/y:online), demonstrating that the longevity of an audience’s emotional investment is highly valuable.

Seeking to maximise direct attention also influences how much of a game follows a suitable pace for the story or experience and how much is solely present to extend playtime. For example, a narrative-focused game only needs to hold a player’s attention for the duration of the story, yet all games on Playstation 4 (2013) have unlockable trophies, which overwhelmingly require the player to engage with elements that don't progress the story, such as a trophy unlocked by “Destroy[ing] all Mr. Raccoons” (Truetrophies:n.y.:online) in the Resident Evil 2 (2019) remake. Mikael Jakobsson says of Xbox Live’s (2002) similar achievement system that “The struggle to collect everything in a game cannot always be described as fun, but the overall experience can still be very valuable” (2011:online). Jakobsson suggests that games use the process of collecting itself to produce positive affect. One could argue it more prudent to redirect this attention at real items and accolades, theoretically matching similar experiential results, with something more palpable.

Johan Huizinga’s book Homo Ludens (1955), originally published in 1938, has become a historical landmark for understanding ‘play’. Indeed, a far later developer of theory around play, Brian Sutton-Smith, describes Huizinga himself as one of “the three truly great twentieth-century play theorists” (2001:ix). Before presenting a definitive definition for Play, Huizinga identifies how it ties to culture and the primal. He recognises that Play may be a place to learn socially and exert built-up energy, but muses on its whimsical presentation throughout nature. In Huizinga’s estimation, these needs could have been satiated through “purely mechanical exercises and reactions. But no, (Mother Nature) gave us play, with its tension, its mirth, and its fun.” (1955:3) This idea asserts that play is primarily an activity for pleasure, but it can induce strong emotions regardless. This is reiterated in Huizinga’s definition of Play:

"Play is a free activity standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as being ‘not serious,’ but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner." (1955:13)

The through line of this definition is that Play is detached from the workings of the real world and exists in its own reality, as far as the physical environment can allow. As such, the player does not need to actively deal with what happened in the play space (assuming no incidents of harm have occurred), for its impact on reality is not explicitly defined. This is not to say that the player has not inwardly shaped themselves, nor that a community has not arisen or been changed during play, but this is not inherently grounded in material interest or profit. The absorption of the player “intensely and utterly” suggests that play cannot be separated from attention and is always tied to affect by the feelings of “tension”, “mirth” and “fun” which underpin it. Therefore, if elements of play appear in a game, the demand for attention is non-negotiable.

Gonzalo Frasca sees ludology as the “understanding of (a game’s) structure and elements –particularly its rules– as well as creating typologies and models for explaining the mechanics of games.” (2003:2) and Mark J. P. Wolf, and Bernard Perron posit that “Searching for the meaning of games is searching for what the game design empowers players to be” (2013:90). The culmination of these ideas forms the basis of Ludology. To first understand games’ fundamental structures and then to examine the experiences they can give to the player. Early games with simple iconography and mechanics act as good reference points, such as Tetris (1984), where the rules and their purposes are clear. The player is empowered as an overseer and coordinator of a limited space. With rotational and transitional influence over falling shapes, their job is to align horizontal rows without the area becoming over encumbered.

Ludology shows that games fit at least some of the criteria of Huizinga’s definition of play, primarily for their focus on rules and structures. However, the design philosophies of many videogames in the modern day make the definition as a whole less applicable. Many games attempt to simulate “profit” and “material interest” as a large part of gameplay and progression. Even in some games that do not demand real money to gain in-game items, this is evident. Warframe (2013), a shooter MMORPG, has a system in which players can trade and market their classes and armaments, which increase in value by season and rarity. As their wealth grows, players can increasingly make more lucrative investments, though endgame rewards (those allowing players to tackle high-level content) may take tens to hundreds of hours of gameplay and market interaction. Platinum, which is temporarily discounted at random intervals for each player, based on daily login rewards can be purchased with real-world money to fast track this process, leading to a similarity with Freemium games.

Freemium games have no upfront cost, but place great emphasis on microtransactions (payments within the game). Elizabeth Evans explains that in this genre “each game settles into a pattern that encourages accessing the game for a short period of time many times a day rather than longer, but less frequent, periods of gameplay” (2016:online). Warframe appears to homogenise this model with polished gameplay, in an attempt to maximise the attention sewn from each individual player. Goldhaber calls attention a scarce resource and says that attracting a large audience is a competitor's solution (1997:n.p). However, Warframe reveals that sustained attention from each individual increases is desirable in the pursuit of this resource too - the sum of two players clocking five hours of attention each, is greater than the sum of four players engaged for two hours each.

In Narratology, pieces of media are recognised as mediators between the audience and a narrative. Murray says that “one might argue that digital games are becoming the assimilator of all earlier forms of media culture. They allow players to take on the characters of print fantasy literature or popular films” (2006:187) This interpretation suggests that the videogame is strongly influenced by previous media, recognising that the changed viewpoint of the audience does not isolate the videogame from its spiritual progenitors. In books, words and rhythms can affect how a book feels, but they are almost always used to illustrate a visual picture and/or to communicate information. In this vein, the ludic elements of a narrative-focused game could be seen as communicators for an overarching context, not the principal reason for a player’s engagement.

Narratology also addresses visual aesthetics as fundamental to a video game’s communicative power. Murray contests prominent ludologist Espen Aarseth’s stance that the game rules and mechanics are singularly relevant in determining how a game is approached. That, in Aarseth’s opinion, Lara Croft is only a model and can be ignored entirely by the player (2004:online). She contends that analysts of this thinking “resist the effort to see their enrapturing abstract symbols as meaningful signifiers linked to the common web of meaning” (2017:online). This proposition suggests that pieces of media are inextricably linked to each of their specific elements. To change any element, including the aesthetics or narrative, can fundamentally redefine the whole piece. Alternate Realities (Pwnisher:2021:video) was a competition for 3D artists to render their own environment and character over a set animation of someone dragging an object. Linus Nelson’s entry (below) realised a character unable to move forward, fundamentally changing the context from one of traversal to entrapment. The theme in narratology is that mechanics are a means to an end and the narrative elements hold great power over how a game is experienced.

Player agency is an area recognised by both Ludologists and Narratologists. Murray states that “When the things we do bring tangible results, we experience… the sense of agency. Agency is the satisfying power to take meaningful action and see the results of our decisions and choices” (1997:159). Murray believes that a person’s ability to influence what occurs in-game helps them to experience positive emotions. “Meaningful” suggests a need for purpose: not just ‘what?’, but ‘why?’ Introducing narrative context for actions can provide this meaning. In Life is Strange (2015) the player character, Max, is held hostage in a chair. On paper, the player has fewer actions and is seemingly deprived of “satisfying power”. In the context of the game, however, each action is desperate and weighted with the situation’s direness. In this sense, the narrative framework is almost exclusively what holds player attention and shows that games can use narrative to seamlessly permit fewer ludic elements and reduced agency.

Robert Caillois proposes that for the player, a game “does not absorb him any less than his professional activity. It sometimes makes him exert even greater energy, skill, intelligence, or attention” (2001:66) Murray echoes this sentiment “In fact, games often ask us to do things that would be work if we were required to do it” (2006:189) These scholars reveal a possible truth, that people enjoy being productive when they are not required to be. Videogames can provide suitable conditions for this hypothesis. In a typical situation, when the player partakes in gameplay, their time investment does not yield necessary (for survival) resources. The player is exercising a skill which is neither monetizable nor particularly transferable to other aspects of life, disqualifying it from having much passive value either. At best, this player has netted a return of positive emotional affect and a particularly niche skill for their attention, yet has little to show outside the game world.

Raph Koster argues, continuing in the vein of agency as a “satisfying power”, that “fun from games arises out of mastery. It arises out of comprehension. It is the act of solving puzzles that makes games fun.” (2004:40). He uses this statement as a springboard to begin differentiating between fun and other positive forms of affect. For one, he clearly interprets fun and fulfilment as separate concepts when speaking of hobbies - “[they aren’t things] we necessarily consider fun. But I derive great fulfillment from these activities.” (2004:144) This puts emphasis upon the nature of leisure time. According to Koster, there is a separation between what is fun at present, and what can be fulfilling in life generally. The former exists in the moment, whilst the latter enriches and betters a person. A problematic idea is that many games “are intentionally designed for you to feel that sense of purpose (...) to walk you through each step” (Adair:n.y.:online) suggesting that they create an artificial idea of fulfilment, which simplifies the stages to make the process more palatable, yet do not necessarily provide long term benefits.

Videogame addiction begins to highlight the issues with how games exist at present and raises questions about the true worth of replayability. “Addiction specialists observed that addict subjects tend to confuse pleasure with happiness when linking emotional states to their addictive activities.” (Gros et al.:2020:online). Pleasure and happiness, they say, occur in different biological systems. Pleasure is activated by short term rewards and is considered more potent “which could explain the stronger drive of the short term gratifications over the quest for medium and long term euthymia” (2020:online). Pleasure aligns with Koster’s view of fun, being only a short-term positive experience. As such, playing games may lead one to seek clear fun and pleasure, whilst neglecting less obviously enriching activities which can lead to happiness and fulfilment; through Gros et al.’s use of the word “confuse” and Koster’s emphasis that unfun tasks are valuable, they appear to see happiness and fulfilment as more intrinsically valuable than pleasure and fun. This begins to identify the problem with videogames which use short-term rewards to entice players into continuous replay loops, for maximum attention. Sutton-Smith shows that there is an additionally a shift in the time and audience of videogames, which may only exasperate this issue:

“Those who play games for the games' sake have to be able to afford the time so to do (Sic). The paradox is that, in this century, the same rhetoric has been applied to the play of children, who, being increasingly disentangled from the work of their parents, have become small aristocrats of conspicuous leisure consumption.” (2001:97)

Smith suggests that with a greater trend toward self-sufficient parents and adults, at least as of 1997 when his text was first published, more young people have been able to consume games in increasing measure, which coincides with a study by Victoria Rideout et al. on the media habits of 8–18-year-olds: “total time spent playing video games increased by about 24 minutes over the past five years” (2010:3) . As such, the attention economy becomes an issue of informed consent, for youth lack concrete knowledge of how their activities will affect their futures. Children especially, who are usually unaware of finance and other serious considerations of the real world, could begin to conflate the short-term gratification of play in videogames with genuine happiness, not for the temporary pleasures they actually represent. Then, the very act of competing for direct attention without hard limits could be seen as perpetuating and exploiting the tendencies of addiction, damaging one's ability to have a fulfilling and happy life. However, by focusing more narrowly on the affect a game produces, rather than the length of gameplay, the player's time could be reallocated towards useful activities and development.

In 2021, Amon Rapp conducted an experiment to explore the ways players are incentivised to stay engaged, using World of Warcraft (2004) as a case study. He categorises overarching types of gameplay that players found engaging into three ‘temporalities’. The first, Rapp names linear temporality “the impossible endeavour of creating an ultimate character” (2021:n.p.), though less specifically, it defines the climb towards higher levels of progression. Circular temporality is a term he attributes to “collecting diversified resources, like herbs and minerals, which can be combined and used to enhance the avatar's equipment or to produce goods” (2021:n.p.). The cycle can keep players in an attention loop, so long as there remains a compelling use for these resources. Warframe’s ‘void traces’ exemplify this idea. They are earned by farming specific enemies during specific missions and used to open relics with a chance for upgrade parts. Borderlands 2 (2012) contains the same type of temporality, with players earning dollars and encountering vending machines for better items, yet dollars are obtained from all enemies and can be acquired simply by engaging with the main story. Therefore, contrary to in Warframe, it is rarely the sole driving force behind player attention. Shared temporality is the attention gained through a player’s sense of community, especially when there are time-limited events. Rapp states that players “feel committed to the collective durations, tempos and periodicities developed within the guild” (2021:n.p.), suggesting that by employing multiplayer elements, a player can become engaged on a level which isn’t wholly about the game itself.

“Trying to add a significant story to a computer game invariably reduces the number of times you're likely to play the game. Literary qualities, usually associated with depth and contemplation, actually makes computer games less repeatable, and more "trashy" in the sense that you won't play Myst again once you've completed it. There's no point.” (Juul:1999:online)

The term “Trashy” refers to a previous discussion by Juul where he identifies that some books are considered lesser if they are only entertaining for one read (1999:online). Here, two assumptions of Juul’s can be identified: ‘videogames have qualities which encourage repeat playthroughs’ and ‘stories actively work against this goal’. Souls-like games, describing games with gameplay inspired by Dark Souls (2011) have key features which encourage players to return to any individual game for many repeat playthroughs. They often contain a myriad of skills and armaments and provide challenges which are intentionally far beyond the difficulty of the average game, giving ample room for players to hone their skills and even to employ personalised twists (like no-death playthroughs). This very subject has birthed an array of YouTube channels, such as Tye Tayler, who have produced countless obscure challenge playthroughs of Fromsoftware’s games. Dark Souls and games like it contain stories, but there is also a great deal of ludic content. In this way, Juul’s conclusion that literary techniques reduce the number of repeat playthroughs is less clear.

For contrast, A Plague Tale:Innocence (2019) provides little way for a player to express their skill, lacking souls-likes’ ranges of weaponry and enemy attack patterns. It follows a rigid narrative and unless a player purposely, or for lack of ability, resists the pull of the narrative and level design, they will find that the solutions to each level are limited. In subsequent playthroughs, they will invariably find that there are few new mechanics and story revelations to be discovered. Harkening back to agency, it would appear that there is a positive correlation between the range of actions a player is given and their duration of attention. The reason Juul correlates story with replayability is likely because heavily narrative-driven games tend to minimise ludic elements as they are not the explicit focus; mechanics may hold attention during less momentous parts of the story, but they are primarily in aid of a narrative’s ability to deliver the intended affect.

This diminishing return from consecutive playthroughs in narrative-focused games is likely the result of no longer facing the unknown. Ross Berger highlights the importance of the question: “Will the protagonist defeat the villain in the most dangerous of circumstances?” and states that “this obligatory scene must be the culmination of art, gameplay, sound, programming (...) It must give players their biggest thrill” (2019:68). The “villain” can be substituted for whatever challenge needs overcoming, but the process is the same. The closer the answer to this question, the more intense affect should become, but if the answer has already been revealed to the player, the question loses a great deal of its impact.

Juul’s specific selection of the word ‘trashy’ attaches a negative connotation to diminished playtime, though this is not without contention. As established by Shouse, affect can continue after a game has ended, maintaining the player’s attention without requiring multiple replays. Further, increased playtime necessarily means that a greater deal of direct attention, established by Goldharber as a limited resource (1997:n.p.), is concentrated on one product. This may be desirable for the company providing the product, but the player is left with less time to experience new games and other aspects of life. By reducing the scope of the ludic experiences presented to the player, there is less incentive to keep replaying and therefore reduced chance for a player to invest more time in any single game than is reasonable. As previously established, narratives are positioned to justify this reduction in ludic content by providing context for the limitations of agency and the play-space, whilst providing the player a new experience in exchange.

Additionally, videogames are uniquely empowered to vary the pace of storytelling and progression. Rafael Chandler defines two categories of level design: Logocentric, which is “linear and controlled and has been plotted out and documented by the designer” (2007:102) and Mythocentric, where “design is wide-open (...) and consists of arenas for player action that have been created by the developers. The player, as author of the core experience, gets to choose the goals and means of the game experience” (2007:108). Whilst categorisation suggests a dichotomy between games of each approach, they are more usefully viewed as a spectrum; some games may have linear sections in an otherwise wide play space, and vice versa. To produce a game which errs toward logocentricity gives the developer a better idea of the playtime and progress arc of players. Alternatively, mythocentric heavy games contain many variables, giving the player more reasons to delay progression, even if they aren’t explicitly trying to extend their playtime.

The linearity of logocentric games reduces the guesswork and contemplation time of players as they determine their path, though other elements can undo this time saved. God of War Ragnarok (2022) fails to communicate clearly the quantity of resources needed for later gear and employs methods of delivering minute amounts of resources, found in breakable objects, which are hardly conducive to completion. With hundreds of these objects across the game, a player compelled to destroy all of them could increase their playtime drastically. The game nests linear paths and story segments, in a range of open play spaces. Even without leaning wholly into a mythocentric experience, one small gameplay detail can affect some players’ entire use of their agency. This emphasises the potential for ludic elements to artificially elongate attention, whilst providing the player with little additional benefit and potentially negative affect, such as discovering that they wasted time on a near irrelevant task.

The infinitely variable combinations of player skill and knowledge can be more broadly labelled ‘Video Game Literacy’. Jeroen Bourgonjon’s aims to define this term, explaining that “People can only be considered literate in a specific discourse when they master the signs and codes in a semiotic context.” (2014:3) Literacy, in this vein, can be understood as the degree to which one comprehends a topic, through its unique signifiers. However, a video game is not always denoted by a range of symbols with internal consistency in the traditional sense. Rather, these symbols are often a conglomerate of real-world information, video game trends and visual contrast. Dead by Daylight’s (2016) breakable doors, are a conglomerate of each of these features (in order of the factors stated): they have visible wear, suggesting weakness, they exist in places where an experienced player would understand that a path should be present and they have more saturated colours. Two of these factors are not just for experienced players. This intuitive demarcation of game elements can help developers reduce the time that a novice player will need to spend on learning how to progress, in turn speeding their passage through each level and reducing the overall attention required to see a game to completion. The demand for skill or innate knowledge without proper indication extends playtime unnecessarily for less veteran players, similarly to the objects in God of War.

Maria-Virginia Aponte et al. state that “when a piece of art is interactive, the aesthetic value comes both from the tension resolution and from the fact that this resolution is a consequence of our choice” (2009:25). “Tension” implies discomfort and strain, however it is usually followed by an eventual relief. This relief cannot be obtained without the aforementioned stress, for relief is by definition a release from an uncomfortable state, making the experience invaluable. The character of Joel in The Last of Us (2013) loses his daughter in the opening sequence and when Ellie, a girl of similar age and personality comes into his care, he keeps his emotional guard up to avoid dealing with the trauma of his daughter. The only way to resolve his turmoil narratively is for him to embrace Ellie and become more fatherly during the journey. The narrative context incentivises the player to vicariously seek the same resolution of tension through their agency, by providing an undesirable status quo and the promise of a release if they continue to progress. This constantly generates attention for so long as the tension is held in the story and does not necessarily require the player to overcome difficult ludic challenges.

Serious Games move the discussion of games as a pastime into the realm of education and utility. They have a “role of conveying some message or input, be it knowledge, skill, or in general some content to the player” (Laamarti et al.:2014:3), yet are not altogether, according to Laamarti et al., void of entertainment, nor absent of the other elements which make up a typical videogame. Within Serious Games could lie a solution to much of what has been established as potentially problematic in this thesis. If a large issue with videogames is infringement into time which could otherwise be used for real-life skill refinement, then involving those skills in a game would minimise or altogether negate the deficit. In some cases, it may even be a better use of one’s time - “playing a technology-based game increased students’ performance in mathematics” (2014:5). If the difficulty of learning and skill acquisition can be integrated satisfyingly into a game, there is reduced demand for what is typically considered to represent skill expression in videogames, such as one’s prowess with movement or their aim. This is evident in the language learning game Duolingo (2012) which requires only that the player can press buttons and navigate menus. The popularity of this application suggests that, as narrative can drive attention, so too can learning.

Procedural Rhetoric was a term coined by Bogost and gives more insight about the potential of serious games: “Procedural rhetoric (...) is a practice of using processes persuasively. More specifically, procedural rhetoric is the practice of persuading through processes in general and computational processes in particular.” (2007:3) To understand this definition, context is required. Bogost saw that a simulation of a secondary school in Tenure (1975) made a “convincing argument that personal politics indelibly mark the learning experience” (2007:2). He thus concluded that one could communicate an idea, or break down a misconception, by presenting it through procedural means. For Bogost, procedures are the rules, or guidelines (depending on how stringent the enforcer(s) of them is/are) of any kind of process. He allows that computers often lack sufficient programming to act with empathy or reasoning, but not that this is an insurmountable flaw (2007:3). He calls upon the teachings of ancient Greek philosophers such as Aristotle and Socrates to conclude that Rhetoric is using “reason to discover the available means of persuasion in any particular case” (2007:18). Bogost also acknowledges that it is easier now than in Ancient Greek times to have intentions lost in translation: “The poststructuralist tendency to decouple authorship from readership, celebrating the free play of textual meanings, further undermines the status of persuasion” (2007:20). Procedural Rhetoric has been understood here as concerns simulations, but it can also be applied to any narrative game which clearly presents an argument or message. Narrative games are after all made up of procedures, stipulated by the computer. By negotiating with the game's ideas, the player can challenge their opinions about the world and acquire novel perspectives. Similar to education, this exchange of value makes the transaction of attention less unbalanced.

Literature Review Conclusion

In summary, the attention economy was established by Davenport and Beck as the competition over a player's limited time and retention. Ash developed how attention is understood in relation to games, using Shouse’s concept of affect, which acknowledges the feeling that persists after an experience. It was understood that play is inextricably linked to attention, because it absorbs the player totally (huizinga:1955:13). Games often contain attributes which are proponents of addiction, such as a focus on short term pleasures, giving developers a degree of responsibility when competing in the attention economy. Usually these pleasures can be traced to ludic elements, whilst narrative-heavy games are less likely to be replayed, as negotiated with Juul’s idea of “trashy” games (1999:online). In this dissertation there is a throughline that many games do not provide the player with enough recompense for their attention, particularly when it is given in excess. However, Bogost’s procedural rhetoric and serious games make a case that some games can help justify the time demanded by giving the player education or valuable insights in return. In the following section, existing games will be analysed in terms of their manipulation and relationship with attention and affect, using the ideas established throughout this dissertation so far.

Case Studies

League of Legends (2009) “generated $1.75 billion in revenue worldwide in 2020, becoming one of the top 10 revenue-generating free-to-play titles in 2020” (Bevan:2022:online). It has also expanded into Esports (competitive gaming) and other projects utilising the intellectual property’s characters and lore. It is an online, top-down, five versus five game, which boasts over a hundred and fifty champions with unique skill sets.

The levelling system in the game uses provides incremental player profile borders and rewards champion shards which can be claimed or dissolved for a resource called blue essence. It continues infinitely, only communicating a player’s play time to others and in this sense is an example of Rapp’s linear temporality, yet the blue essence itself represents a circular temporality (2021:n.p.). The player acquires it through playtime and subsequently spends it on champions to expand their roster. Winning a game daily grants a small bonus, though this is also problematic because a win is never guaranteed. In the pursuit of earning their one win for the day, a player may be forced to play through multiple defeats first. With games averaging, (as of patch 13.1) around 25-30 minutes (Leagueofgraphs:2023:online), this is potentially a huge drain on a player’s time each day.

League of Legends operates seasonally, introducing yearly revamps and resetting each player’s competitive rank. The game has complicated rules and a learning curve which becomes steeper as other players become more proficient, making mastery a endless process and using satisfaction as an allure (Koster:2004:40). Furthermore, within the game, there is no narrative through line and this lack of a definitive end goal can keep players trapped. With no barrier to play, such as the exhaustion of all quests through completion or end of the story, the player must use their discipline to break from the habit of playing. However as previously observed, this is something which is intentionally made difficult by the game’s design.

A Plague Tale: Innocence features princess Amicia, skilled with a slingshot, and not naïve to the death and hardship of the world she lives in. The goal of the game is to take her brother, Hugo, to get help for a potentially lethal curse, whilst pursued by unfamiliar antagonists. The curse, whilst not on a countdown in any ludic sense, is a source of tension (Aponte et al.:2009:25) in the narrative. The developers can incentivise the player to engage with this sense of urgency without having to set physical time constraints through the dialogue and presence of Hugo, so long as the relationship becomes deep enough over time. Jacqueline Burgess and Christian Jones say that “Players enjoyed developing relationships between their PC and an NPC, and when deep relationships were established, (...) players expressed wonder and high levels of engagement.” (2001:online) Developers can also dial back ludic elements and lean into logocentric design to increase the likelihood that a player’s actions match the stakes set out in the plot. When Kratos in God of War has to track down his son Atreus in a maze, there are no resources to be found and there are only two diverging paths at each junction - an absence of ludic elements and agency for narrative clarity. League of Legends instead exercises little restraint in its ludic elements. The game continually adds new champions and changes, spurring on new interactions between abilities and leading the game’s pace to fluctuate and shift regularly, though it is not clear that this is always intentional. Arbitrarily maintaining player attention allows the company to increase profits. If players identify the skins and champions as items they will make significant use of, they are more likely to self-justify spending their money. Unfortunately, there appears little concern for how the player’s attention and feelings of affect are manipulated once in-game.

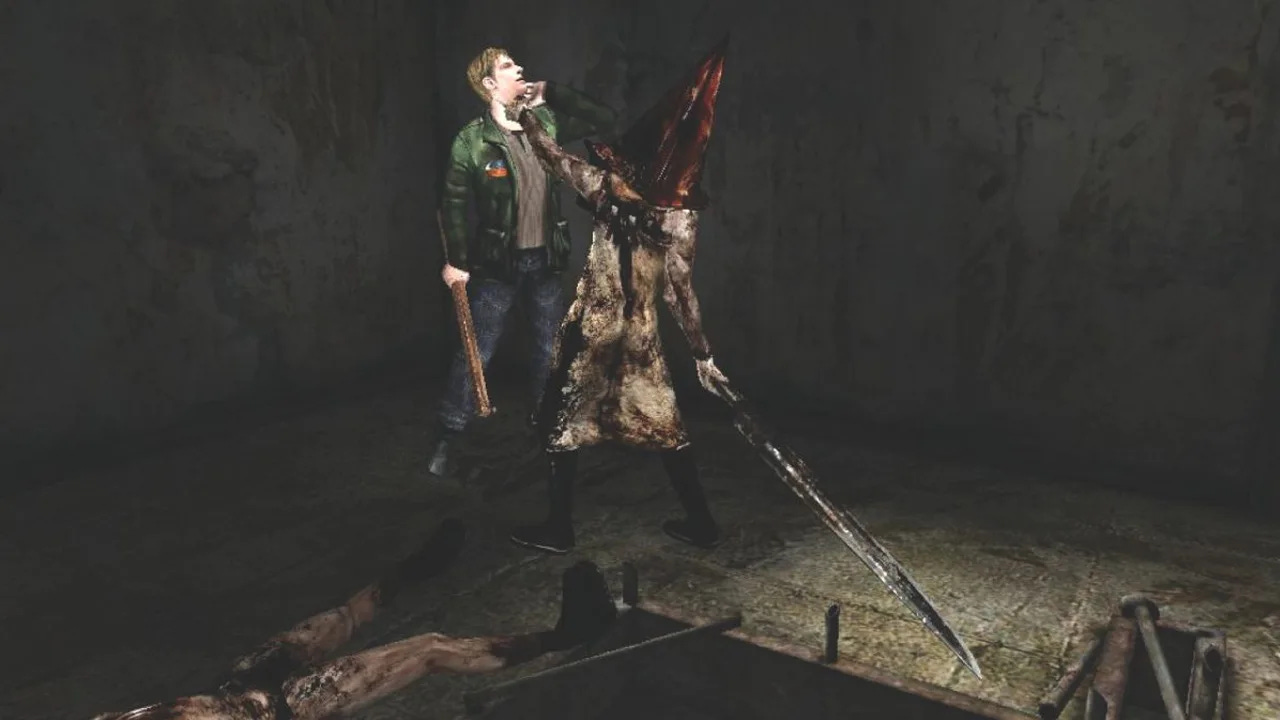

Silent Hill 2 (2001) makes clear that it does not exist to make the player feel short-term pleasures. During the opening cutscene, James Sunderland examines himself in the mirror of a grotty bathroom, his eyes shrouded by darkness. He recalls a letter from his wife, who he knows to be deceased, in which she states “I’m alone there now. In our special place… Silent Hill”. Very quickly, themes of depression and potential delusion are established. In Huizinga’s understanding, play consists of “mirth” and “fun” (1955:3), which appear contrary to the themes established by the game. However, in place of traditional play, the game uses procedural rhetoric (bogost:2007:3) to engage players with difficult questions about morality and grief through narrative elements. Media which encourages players to engage in the formulation of their own opinions of the story’s message and process emotions in a safe environment may prepare them for the challenges of life, resulting in greater long-term happiness (Gros et al.:2020:online) and fulfilment (Koster:2004:144). League of Legends lacks such ambiguity. One wins or loses and must simply improve mechanically or expand their knowledge of the game, with both lacking obvious utility outside the game’s immediate parameters and neighbouring games.

Conclusion

This dissertation asserts that by perpetuating and normalising linear and cyclical temporalities (Rapp:2021:n.p.) either indefinitely or for great amounts of time, attention is normalised as a resource to be harvested with little concern for consumers. The capture of attention for long durations can intertwine with addiction when the player receives only short-term pleasures or fun, rather than happiness and long-term fulfilment. This problem can be offset partially if a game provides players with useful skills, knowledge and/or contemplation for the real world. Additionally, involving narrative as an essential part of the game’s tension and a large factor in the player’s engagement, repeat playthroughs don’t have the same unknown (Berger2019:68) making them less appealing (Juul:1999:online). With the goal of moderating attention, this is actually favourable. Ludic distractions and lack of guidance can artificially truncate playtime, whilst giving little obvious value. Ultimately, many games are designed to capture too much attention from the player, without sufficient compensation for their time and by moving towards persuasion, education and narrative, a better balance can be achieved.

Bibliography

Reference (Texts):

Aarseth, E. (2004) Genre Trouble At:

https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/genre-trouble/ (Accessed 4.12.2022)

Adair, C. Cam’s Story At: https://gamequitters.com/cam/ (Accessed 1.2.2023)

Ash, J. (2012) ‘Attention, Videogames and the Retentional Economies of Affective Amplification’, Theory, Culture & Society

Aponte, MV., Levieux, G., Natkin, S. (2009). Scaling the Level of Difficulty in Single Player Video Games Berlin: Springer

Berger, R. (2019). Dramatic Storytelling & Narrative Design: A Writer’s Guide to Video Games and Transmedia (1st ed.). CRC Press.

Bevan, J. (2022) League of Legends Revenue and User Stats (2022) at:

https://mobilemarketingreads.com/league-of-legends-revenue-and-user-stats/ (accessed 19.01.2023)

Bogost, I. (2007) Persuasive Games : The Expressive Power of Videogames. MIT Press, Cambridge

Bourgonjon, J. (2014) The Meaning and Relevance of Video Game Literacy (issue 5) Purdue: University Press

Burgess, J., Jones, C (2001) “I Harbour Strong Feelings for Tali Despite Her Being a Fictional Character”: Investigating Videogame Players’ Emotional Attachments to Non-Player Characters At: http://gamestudies.org/2001/articles/burgessjones [Accessed 19/01/2023]

Caillois, R. (2001) Man, Play and Games Illinois: University Press

Cover, R. (2006) Gaming (Ad)diction: Discourse, Identity, Time and Play in the Production of the Gamer Addiction Myth At: http://gamestudies.org/06010601/articles/cover (Accessed 20/01/2023)

Davenport, T.H., Beck, J, C. (2001) The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Buisiness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press

Evans, E. (2016). The economics of free: Freemium games, branding and the impatience economy. Convergence, At: https://journals-sagepub-com.ucreative.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1177/1354856514567052 (Accessed 19.01.2023)

FORBES. (n/y) Forbes Profile - George Lucas At: https://www.forbes.com/profile/george-lucas/?sh=2a3041076e63 (Accessed 19.01.2023)

Frasca, G. (2003) Simulation versus Narrative: Introduction to Ludology Routledge

Gros L, Debue N, Lete J, van de Leemput C. (2020) Video Game Addiction and Emotional States: Possible Confusion Between Pleasure and Happiness? At: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6996247/ (Accessed 10.11.2022)

Huizinga, J. (1955) Homo Ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

Jakobsson, M. (2011) The Achievement Machine: Understanding Xbox 360 Achievements in Gaming Practices. Available at: http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/jakobsson [Accessed 11/01/2023]

Juul, J. (1999) A Clash between Game and Narrative At: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/3711462/a-clash-between-game-and-narrative-jesper-juul (accessed 20.11.2022)

Leagueofgraphs. (2023) Game Durations At: https://www.leagueofgraphs.com/stats/game-durations (Accessed 25/01/2023)

Murray, J. (1997) Hamlet on the Holodeck Cambridge: MIT Press

Murray, J. (2006) Toward a Cultural Theory of Gaming: Digital Games and the Co-Evolution of Media, Mind, and Culture. Popular Communication. Georgia

Murray, J. (2017) why some players and critics still cannot tolerate narrative in games At: http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/janet-murray-on-why-some-players-and-critics-still-cannot-tolerate-narrative-in-games/ (Accessed 25.11.2022)

Rapp, A. (2021) Time, engagement and video games: How game design elements shape the temporalities of play in massively multiplayer online role-playing games (JournalVolume 32 Issue 1)

Ruppert, L. (2020) At: https://www.gameinformer.com/2020/11/23/one-dev-played-over-175-hours-of-cyberpunk-2077-and-still-hasnt-beaten-it (Accessed 15.10.2022)

Shouse, E. (2005). Feeling, Emotion, Affect. M/C Journal, 8(6). At: https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2443 (Accessed 13.11.2022)

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Switzer, E. (2021) At: https://www.thegamer.com/league-of-legends-arcane-story-universe-runeterra-wild-rift/ (accessed 12.12.2022)

Truetrophies. (n.y.) Resident Evil 2 Trophies. At: https://www.truetrophies.com/game/Resident-Evil-2/trophies (Accessed 06/02/2023)

Wolf, M, J. P. Perron, B. (2013) The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies. Taylor & Francis Group

Reference (Media):

Borderlands 2 (2012). [CD][Download] PC, PS3, Xbox 360. 2K Games:California

Dark Souls (2011). [CD][Download] PC, PS3, Xbox 360. FromSoftware Inc.:Tokyo

Dead by Daylight (2016). [Download] PC, PS4, PS5, Xbox One, Xbox Series X. Behaviour Interactive:Montreal

Disney. (1923). [Brand]. The Walt Disney Company:California

Duolingo. (2012). [Download] Mobile. Duolingo Inc.:Pittsburgh

God of War. (2018). [CD][Download] PC, PS4. Santa Monica Studio:California

God of War: Ragnarok. (2022). [CD][Download] PC, PS4, PS5. Santa Monica Studio:California

League of Legends. (2009). [Download] PC. Riot Games:California

A Plague Tale: Innocence. (2019). [CD][Download] PC, PS4, PS5, Xbox One, Xbox Series X. Focus Entertainment:Paris

Playstation 4. (2013). [Console]. Sony Entertainment:California

Life is Strange. (2015). [Download] PC, PS4, Xbox One. Square Enix:Tokyo

Resident Evil 2. (2019). [CD][Download] PC, PS4, Xbox One. Capcom:Osaka

Star Wars. (1977). [Franchise]. The Walt Disney Company:California

Silent Hill 2. (2001). [CD] PS2. Konami Digital:Tokyo

The Last of Us. (2013) [CD][Download] PS3. Naughty Dog:Virginia

Tetris. (1984). [SD card] Game Boy. Nintendo:Kyoto

Warframe. (2013).[Download] PC, PS4, PS5, Xbox One, Xbox Series X. Digital Extremes:London

World of Warcraft. (2004). [Download] PC. Blizzard Entertainment:California

Xbox Live. (2002). [Network]. Microsoft:Washington

Reference (Images):

Breakable Door in Dead by Daylight (n.y.). Breakable Walls. At: https://deadbydaylight.fandom.com/wiki/Breakable_Walls (accessed 02.02.2023)

Cyberpunk 2077 World (2021). Cyberpunk 2077 is better than ever but is that enough to save it? At: https://www.techradar.com/news/cyberpunk-2077-is-better-than-ever-but-is-that-enough-to-save-it (accessed 03.02.2023)

Homoludens graphic (2022). HomoLudens. At: https://www.facebook.com/sportmarvin04/ (accessed 12.12.2022)

Linus Nelson Alternate Realities Entry (2021). Top 100 3D Renders from the Internet's Largest CG Challenge | Alternate Realities. At: https://youtu.be/iKBs9l8jS6Q (Accessed 03.02.2023)

Silent Hill Pyramid Head vs James Sunderland (2020). Silent Hill 2 mejora visual y sonoramente en esta actualización hecha por fans. At: https://es.ign.com/silent-hill-2-pc/168338/news/silent-hill-2-mejora-visual-y-sonoramente-en-esta-actualizacion-hecha-por-fans (Accessed 03.02.2023)

Star Wars Franchise-Wide Poster (2023). Star Wars Movies in Order: How to Watch Them Chronologically. At: https://www.ign.com/articles/star-wars-movies-tv-shows-chronological-order (accessed 03.02.2023)

Taurus Demon Boss in Dark Souls (N.Y.). Taurus Demon At: http://darksouls.wikidot.com/taurus-demon (Accessed 03.02.2023)

Reference (Videos/Creators):

Pwnisher (2021). Top 100 3D Renders from the Internet's Largest CG Challenge | Alternate Realities. At: https://youtu.be/iKBs9l8jS6Q

(Accessed 03.02.2023)

TyeTaylor. At: https://www.youtube.com/@TyeTaylor (Accessed 20.11.2022)

Great depth on a number of games here. Looking forward to see how your thoughts have developed when you come to revisit this piece!