Videogames Should Not be Games

A panoramic exploration of the way that games perpetuate addiction, making reference to the Attention Economy and Gamification, plus a call for more ethical reforms.

Videogames should not be games first, nor second. Perhaps not even third…

Over the recent years, we have become increasingly entangled in the Attention Economy, a notion which is gradually being acknowledged. However, this rising economy has been in effect for a long time. It may well be the most damaging aspect of human life in the modern age; it opens the gates to all manner of social and political upheaval and causes direct psychological harm to individuals. Many factions have recklessly weaponised the findings of behavioural sciences in order to squeeze out every last drop of attention possible, though we most often point fingers of blame at this practice in gambling and social media.

As a result of this brazen assault on the human psyche, we have not only the quantitate sum of time lost to addictive behaviours, but myriad attention deficit disorders. The antidote? Self-help, one of the fastest growing non-fiction genres. Individual responsibility is empowering and one antidote to the issue, yet addiction is the greatest barrier to individual responsibility. It is like being faced with a locked box, with its own key inside. One might notice a problem here…

A systemic issue

In the Lord of the Rings book (extremely minor spoiler for those who have seen the films) Faramir never sees the ring. He explicitly refuses even the temptation. In my opinion, this is far more effective than in the film where Faramir simply restrains himself, even after seeing the ring. The book version teaches us that the external world warps us and that we would be wise not to pit our self restraint against temptation needlessly. Even Frodo fails in this internal battle. Practically, this means that when we discover a broad societal trend with temptation as its driving mechanism, that insisting on personal restraint may only go so far:

A neutral state, where the person puts a “healthy” (to be defined) amount of time into an activity, is when the temptation surrounding the thing is equal or less than the amount of self-restraint they have at any given moment. Addictiveness is effectively just the state where “temptation” consistently has a higher value than “self-restraint” throughout a person’s days. This by extension gives two broad access points in addressing an addiction. To increase one’s self-restraint, or to reduce temptation. Temptation is a composite of the object of attention, negative emotion, dopaminergic release etc. All of these mentioned elements are difficult to address, yet one of them is not constrained to the individual: the object of attention. This could be a game, or a film, or even work. By making this element less tempting, it echoes out and reduces the total temptation for everyone.

The following is a hypothetical case study. It is intended to demonstrate logic rather than science, and will take great liberties in order to demonstrate the concept:

Five different people are put in separate rooms with 1) a dry educational book that is necessary for their studies and 2) an object that is entertaining. Two are feeling many negative emotions (contributing highly to temptation for a leisure activity), the others only a slight malaise. On the first day, all are given a very intriguing object such as a TV with all the usual streaming services (high temptation value). All five choose the TV rather than studying which they know they ought to do. The next day, each has defaulted back to the same level of negative emotion that they had the day before. This time the product is less interesting, a TV with only a few channels and none of those exciting (low temptation). The two people who are incredibly down, even then continue to indulge the coping mechanism, because their negative emotion only seeks respite. However, the other three in this scenario are finally able to resist the temptation and read. By reducing the temptation in the object of attention, they muster up sufficient self-restraint to counter the coping mechanism and change their focus to something more productive.

There are of course many factors beyond negative emotion in determining whether someone gives into an addictive behaviour. Additionally, by removing one object of interest, it may well be replaced with another of higher temptation, but this approach at least offers a pathway out and a chance at choosing a favourable activity. Now let’s discover where videogames fall into this sum:

Just how addictive are videogames?

Videogames have thus far remained relatively comfortable from criticism in the addiction space, indeed their overindulgence has not yet been recognised by the American Psychiatric Association as a disorder. Rather they are placed in with a broader category:

“[The] committee considered adding video game addiction to the most recent diagnostic manual but ultimately chose to wait for further consideration (…) Video game addiction falls into the category of Internet gaming disorders (IGDs), which have been strongly correlated with motivational control issues and are regularly compared with gambling”

Videogame addiction has stayed in the domain of occasional studies and concerning headlines, whilst the prevalence of the “one more game” meme throughout the gaming community clearly indicates a large problem.

This may all be making me sound like a technophobe, but as someone who has studied videogames, been part of many circles of chronic gamers and struggled with this addiction, I have seen first-hand how much of an impediment to a fulfilling life they can be. My hope is only that we ethically guide this medium and be conscientious of its effects.

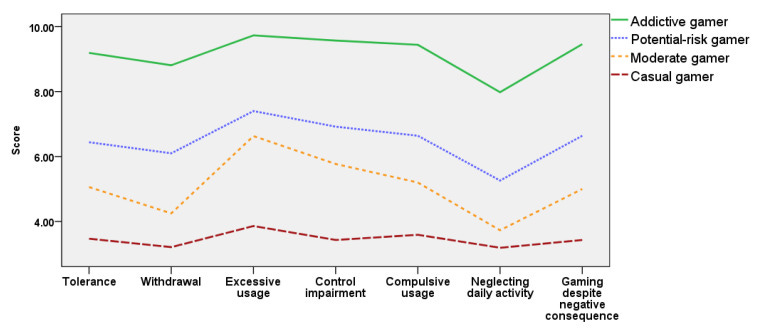

A worrying aspect of videogames is that their addictiveness seems to be most heavily defined by excessive use. It ranked as the most prevalent issue in the assessment of addictive gaming, across all types of gamers. This means that even without the direct health issues which make substance abuse so obviously dangerous, videogames are able to rise to similar concern by virtue of their long-term stranglehold on attention. Again, although the APA has not yet listed it as an addiction in its own right, it is being strongly considered.

It also appears that the overall problem is being diminished by virtue of definitions. One study placed the bar for moderation as up to 3 hours:

“49% of Americans game in moderation, spending no more than 3 hours gaming in a row. Only 6% of Americans report regularly marathoning games for more than 13 hours”

If three hours at a time is when we consider videogames excessive, in a world where many are struggling to find time for all of their commitments, there may be a discrepancy between what scientific bodies deem problematic and the practical truth. And if we can place “only” before twenty one million game marathoners (6% of the US population), it raises questions about our definitions of health and addiction.

It would also appear that of those who regularly play videogames, the percentages shoot up from the comparative global studies. This is practically self evident, but it is of grave concern when one considers that videogames are ever manoeuvring themselves towards mass appeal and mass distribution, increasing their reach gradually from a once predominantly male demographic. I do not think videogames should be an exclusive club, but they should ensure that they have strong ethical foundations before turning efforts towards expansion. Unfortunately, it appears that this is already in effect:

“There were 2.69 billion video game players worldwide in 2020. The figure will rise to 3.07 billion in 2023 based on a 5.6% year-on-year growth forecast.”

Gamification

Behavioural Psychologists have identified that people respond favourably to games and forms of play. This has lead to a practice known as Gamification, which employs game-like features in non-game environments. Our minds are wired to anticipate rewards when trends arise, so if each time that we press a button, we receive a coin, our brains create a behavioural connection to encourage the repetition of that action. If we keep receiving rewards (even better if it is based on probability), then those networks are bombarded with affirmative information. Ever, the biggest competitors in the attention economy seek a greater monopoly on the minds of a global population and this concept of gamification has become one of the most effective tools:

“Gamification is not just a fad; it’s the fate of a digital capitalist society. Anything that can be turned into a game sooner or later will be.”

The world is gamified to such an extent that to enter a domain of gameplay is to make ‘Inception’ out of the already existent games that play out in life. That is to say, that when we play a videogame, we are playing a game within the already gamified structure which superimposes itself into every element of our lives. The Inception film warns about escapism through the plane called “Limbo”, the most desire fulfilling, yet mentally imprisoning aspect of the dream world. Its principal danger is that it can make one forget that they are in a dream. Given the subtle ways in which our lives are gamified, it can become very difficult to discern what is structured and what is based in the relative randomness of life. This dichotomy might be a part of why we find life so overwhelming; we must constantly be assessing whether we are engaging in someone else’s game. The following video is in Spanish, but in essence Oscar Garcia explains that even the colouration of cookies is a way in which life is subtly gamified.

Videogames, in this context can become very attractive, because the player knows what they are dealing with. This is a game of consent on the surface. Our brains have a proclivity towards, and have been infinitely (for all intents and purposes) conditioned into liking gamic structures.

Whilst the player is highly unlikely to confuse themselves with their character, as the “immersive” tag often implies, the resulting behaviour of hardcore gamers is of a kind which makes the distinction mute. The player may not literally think they are Yasuo from League of Legends, but they may still damage their relationships through obsession:

“Harm scores were consistently higher for parents of children with problem gaming than parents with children in the at-risk and non-problem groups (…) This pattern of results was also observed among partner respondents”

Dependency on a substance or product allows the medical industry (especially in the US) to churn out immense profits. Whilst in some cases we are able to choose which products we purchase and consume, for-survival goods present too grave an option. This is because the monetary value of the product is directly correlative with one’s will to life (with adjustments for debts imposed on one’s family). Dependency is therefore a metric of monetary value. Videogames are not dealing with real life or death in the immediate, but they do play on the already existing game-orientated minds of the population.

The ethical landscape

It is ethically problematic for game developers to be enablers of those who are already being manipulated from all angles. Sometimes an enabler encourages an addiction to consolidate their control over the person they are enabling, but often it is done of compassion. Trying to help someone who is struggling by giving them what they want, rather than what they need. At worst, addictive videogames represent the development of the strongest drug possible and selling it to the already addicted. At best, they are a friend who thinks that feeding their friend’s addiction is kind, because the enabler cannot conceptualize the harm done over the long term.

Some of the major companies that are explicitly corrupt, with their many gambling elements, are easy targets. However, they distract from the broader issue, and for every huge company that falls, two equally corrupt will take its place. In this way, the videogame industry has found itself in a very comfortable position… All of its most common malpractices are buried under the spectacle of the industry whales. To truly rework the industry into something that is more ethical, we must establish fundamental principles by voting with wallet and with discourse. This may seem futile, but as ever, change begins with a spark. I believe that of all of the branches of the attention industry, videogames are most likely to bend to our desired outcomes with enough pressure.

It is not enough therefore, to judge game companies by their ethical practices towards staff and in monetization. If they are sending out an addictive and damaging product (by myriad metrics), whether by intention or not, there is a breach of ethics. It may be prudent to create an example by drawing eyes to the addictive practices of more obviously malicious companies as a method of dissuading that behaviour across the industry. Or by appealing to the human side of those companies that have appeared to follow moral practices, only failing to catch some of their inconsistencies.

Gameplay in servitude to a goal

It is in this section that the idea of videogames prioritising their gamic features will be interrogated, in line with the initial statement of this essay. I will attempt to illustrate why the gamic focus should be down-tuned, in order to reduce the addictiveness of the products and give the gaming community a more easily regulated experience. Some elements and experiences would be lost by this process, but they seem to pale against the humanitarian gain. This is really a panoramic view. Deeper explorations of the medium and the how of its manipulation of attention can be found in my dissertation on the subject.

The videogame industry wears its addictive properties as a badge of honour. It boasts how long each product will capture the player, whether divided by playthroughs (the time to complete a game with an end point), constant downloadable content (dlc) updates or in terms of skill development in online competition. FromSoftware are a company who make difficult and grandiose videogames. Two I have played: Bloodborne and Elden Ring, and I am very fond of them. They have placed high value on creative expression, trust in employees and ambitious worldbuilding. All are admirable traits. I have little doubt that the company is largely focused on producing the best art possible. However, they seem to encourage players to invest great amounts of attention into developing their skills and exploring the world. Even their dlc’s are known for their immensity. This emphasis on the scale of gameplay is concerning, not because it does not elevate the artistic expression, but because it increases the attention sink required.

Conversely, The Order 1886 received much criticism on the grounds that its playthrough time, averaging five to seven hours, was simply not enough. Given the pricing this had some justification, but it speaks to a deeper issue. It was a game oozing with visual fidelity and ambition. By most standards aside from playtime, it was an impressive game. Yet many cried out that it didn’t satisfy their expectations in the playtime metric.

Ludologists and Narratologists, seeing play (ludic elements) and narrative respectively as the highest calling of videogames, have argued endlessly over the purpose of the medium, but rarely concern themselves with the ethical implications that each ambition contains. Videogames may include “games” in their semantic compound and display all of the associated states of play, yet they fit most comfortably into the ethical considerations of the entertainment industry in common discourse. We more often discuss videogames alongside films and series, than with board games and sports matches (though e-sports have been fighting for this association). As such it is prudent to make reference to the former category to of media when discussing videogames’ overall impact.

Videogames have marked a divergence from other similar media. Books are not books first. One doesn't read the pages and think “hmm, this book needs to be more book-like”. Films challenge the truth in this idea, in that some films are intentionally: “big monsters, no story”, but it would still be difficult to strip them down to just their mechanical/technical barebones without losing the entertaining element. In these aforementioned media, the products are judged first by their total result and then the minutia is disentangled in order to appreciate or understand how such a level of quality was achieved. Essentially, when we interrogate films, or series, or books, we most often ask how they accomplish the goal of translating plot beats into a well rounded story; we are more likely to recognise them as the unison of their elements. Videogames that focus on affect (emotions and lasting experience), rather than the immediate gratification derived from gameplay, are at least in line with the ambitions of previous media and are not generating novel problems.

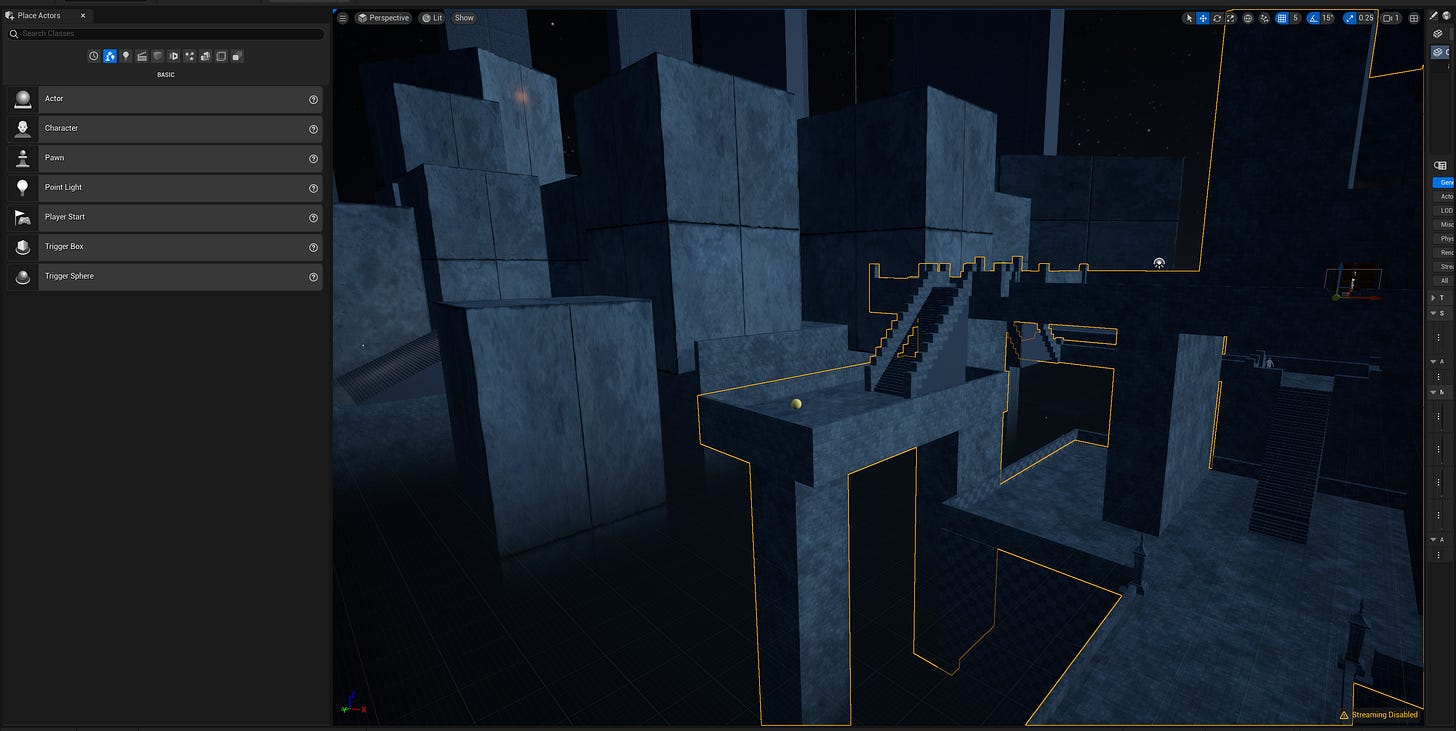

Many videogames, in contrast, focus on mechanics as if they are ends in themselves. A game that dresses itself poorly can still be played, indeed it will often still be considered an entertaining experience. The production pipeline of a videogame is indicative of this. Game developers will produce a greybox, which contains all of the mechanical and spacial aspects of the game in simple blocks, without any of the highly detailed assets which take a longer time to produce. This is where preliminary playtests will occur, with players commenting on the quality and “fun” of the mechanics, ability to navigate etc. Effectively it is a quick sketch, to be painted over.

The game, superhot, plays into this very heavily, with its incredibly minimalist style, supported by an interesting mechanical gimmick (everything is set in slow motion and time only speeds up when the player moves).

We know that gamification has been largely influenced by psychology, thus there is a neurological and observational precedent to call ludic elements addictive. Concerns arise when videogames reveal that their core ingredient is inherently able to override one’s impulse control and decision making. Anything containing such a high quantity of such an ingredient will be addictive by virtue of its presence: think nicotine, or caffeine. As a general rule, the more ludic a game becomes, the more attention it is likely to command.

Solutions

Though this is by no means an exhaustive list of the reasons for why I believe a shift is needed, my proposition is that videogames should resign to narrative experiences. Though there is also a case for making them into academic learning tools which I will discuss in future. Videogames should not be primarily ludic experiences. This is not in reference to definitions, but to ethics. The ludic approach has been a project of manipulative monetisation strategies and infinite gameplay loops, whilst the narrative approach has largely continued on a track adjacent to films and series.

As ever, I am hesitant to recommend legislative measures to punitively ensure this turn toward narrative and learning. By my estimation, the best solution is to support those videogames financially which are in tune with this general direction for the medium and to move away from or critique, in a constructive fashion, the more aggressively addictive videogames. This is effectively just the concept of voting with one’s wallet.

I implore us to take steps to expand the literature in this area and become more discerning in our consumption. Not only for the sake of ourselves, but for the rapidly spreading gaming community at large.

Leon,

A revolution is pending. It's a revolution in attending. We attend to those things which we choose to prioritize.

Prioritizing the arc of our lives while also prioritozing our human family, that's like voting with our attention.

Here I've said in a very few words what others have said much more eloquently in thick well-referenced books.

I hope this makes sense.

Thank you for your good work.

Don't stop now!

mark spark

.

A thought provoking analysis of addiction in gaming and some great observations. Well worth the time to read!